Hopfield Network as Wordle Solver

Biologically Plausible Associative Memory for Recalling Missing Word Patterns.

Motivation

What happens when you encounter a partial word like “d__ty” in your mind? Your brain doesn’t randomly guess—it systematically explores possibilities like “deity,” “dusty,” “dirty,” each triggered by spreading activation through your memory network. This cognitive process inspired me to explore whether modern Hopfield networks could model human-like word completion.

While existing Wordle solvers achieve 95%+ success rates using information theory or reinforcement learning, they lack biological plausibility. Can we build a system that solves Wordle the way humans might—through associative memory retrieval rather than exhaustive optimization?

Background

1. Wordle and the Mathematical Approach.

Skip to Hopfield part if you already know what is a Wordle and Information Theory application for it.

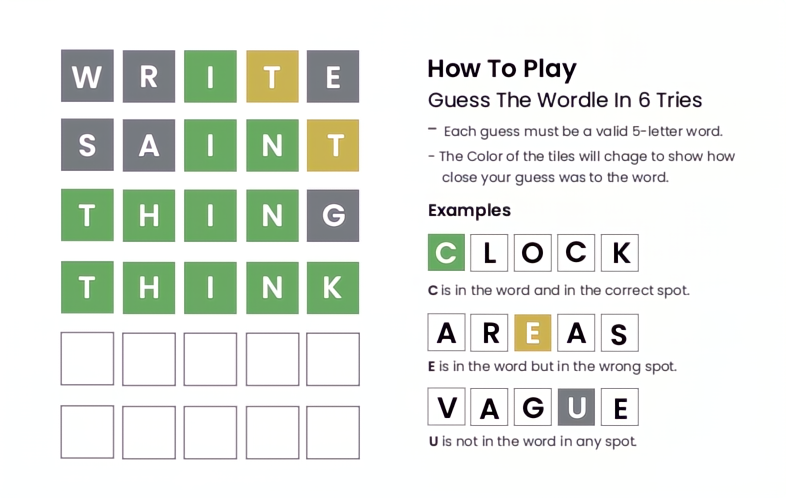

“Wordle is a web-based word game created and developed by the Welsh software engineer Josh Wardle. In the game, players have six attempts to guess a five-letter word, receiving feedback through colored tiles that indicate correct letters and their placement. A single puzzle is released daily, with all players attempting to solve the same word. It was inspired by word games like Jotto and the game show Lingo. Bought and hosted by The NY Times.”

- From Wikipedia.

Information Theory - How it’s used in solving Wordle: (3blue1brown explanation)

Briefly, the optimal Wordle strategy maximizes information gain per guess. Each guess partitions the solution space, with entropy measuring uncertainty:

\[E = -\sum_{i} p_i \log_2 p_i\]Example: Starting with “SALET” provides ~5.9 bits of information, reducing 2,315 possible answers to ~60 on average. However, this approach requires:

- Perfect knowledge of word frequencies

- Exhaustive similarity computations

- No memory or attention limitations

Rank One Approximation - from the paper Rank One Approximation as a Strategy for Wordle

“The motivation behind a low rank approximation comes from determining the dominant direction of a matrix. In statistics this approach is referred to as “Principal Component Analysis” and is used to determine a line of best fit through a set of data. The principal direction can be helpful in data analysis and making predictive models. In the context of Wordle, the principal component of a set of words will be found and interpreted as the best representation of the set. By then finding the word closest to the principal component it can be interpreted that this word is ‘most representative’ of the set. This method will find a representative word without needing to consider letter frequency.”

Theory

A rank one approximation begins with applying single value decomposition to a matrix \(A\). Single value decomposition is a way of factoring a matrix \(A\) into the following form:

For an \(m×n\) matrix the factors \(U,S\) and \(V\) are defined as follows:

\(U := m×m \text{ matrix whose } \textbf{columns} \text{ are the left singular vectors } u_i\) \(S := m×n \text{ matrix whose } \textbf{diagonal entries} \text{ are the singular values } \lambda_i\) \(V := n×n \text{ matrix whose } \textbf{rows} \text{ are the right singular vectors } v_i\)

where:

\(u_i := \text{the eigenvectors of } AA^T\)

\(\lambda_i := \text{the eigenvalues of } AA^T \text{ (or } A^TA\text{)}\)

\(v_i := \text{the eigenvectors of } A^TA\)

The eigenvectors for both \(U,S\) and \(V\) are arranged in descending order according to their corresponding eigenvalue. If $m=n$ that is to say the following:

\[A =\begin{bmatrix} u_{11} & \dots & u_{1m} \\ \vdots & & \vdots \\ u_{m1} & \dots & u_{mm} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \lambda_{1} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & \lambda_{2} & \dots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & \lambda_{m} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v_{11} & \dots & v_{1n} \\ \vdots & & \vdots \\ v_{n1} & \dots & v_{nn} \end{bmatrix}\]Where:

\[\lambda_1>\lambda_2...>\lambda_m\]and

\[u_i = \begin{bmatrix} u_{1i} \\ u_{2i} \\ \vdots \\ u_{mi} \end{bmatrix} \text{ and } v_i^T=\begin{bmatrix} v_{i1} & v_{i2} & ... & v_{in} \end{bmatrix} \text{ correspond to } \lambda_i\]Factoring \(A\) into the components \(U,S\) and \(V\) is known as Single Value Decomposition of the matrix and is a question of determining eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the two matrix products and placing the results in their corresponding index. From here, a rank one approximation of \(A\) considers the singular value \(\lambda_1\) and the corresponding vectors \(u_1\) and \(v_1\) to approximate the matrix \(A\). The method proposes that these two column vectors and eigenvalue is the best approximation of the matrix \(A\).

\[A ≈u_1\lambda_1 v_1^T\]References:

- Sauer, Timothy. “Eigenvalues and Singular Values.” Numerical Analysis, Pearson, Boston, MA, 2006, pp. 566–579.

- James, David, et al. “Singular Vectors’ Subtle Secrets.” The College Mathematics Journal, vol. 42, no. 2, 2011, pp. 86–95., https://doi.org/10.4169/college.math.j.42.2.086.

In this work, I applied LORA based on the fact that it can applied on a retrieved set of words (fitting for my initial idea).

2. Brief background on Classical Hopfield Networks

Associative memories are one of the earliest artificial neural models dating back to the 1960s and 1970s. Best known are Hopfield Networks, presented by John Hopfield in 1982. As the name suggests, the main purpose of associative memory networks is to associate an input with its most similar pattern. In other words, the purpose is to store and retrieve patterns.

Think of a Hopfield Network as a magical photo album where showing a torn photograph automatically reconstructs the complete original image. This is exactly what these networks do—they’re associative memories that can recall complete patterns from partial or noisy inputs. In our case, they can complete “D__TY” → “DEITY” by associative recall rather than exhaustive search.

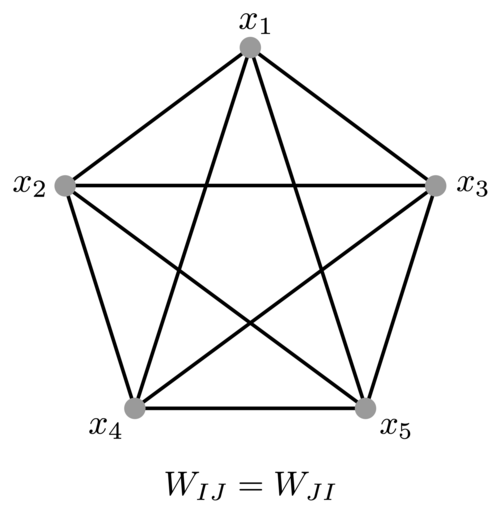

The components typically includes:

- Symmetric weights which can be represented as an undirected graph (the connections from neuron i to neuron j is the same weight vice versa)1: \(W_{ij} = W_{ji}\)

- Binary neuron states: 0/1 (binary), -1/+1 (bipolar)

- No self-connections: \(W_{ii} = 0\) (neurons don’t connect to themselves)

Example: To store the word “DEITY”, we encode it as a bipolar vector where each position represents a letter:

"DEITY" → [+1, +1, +1, +1, +1] (simplified 5-dimensional representation)

The network creates connections between neurons such that this pattern becomes a stable memory state.

Mathematical formulation for Word Completion

Given: N word patterns to recall: \(\{x_i\}_{i=1}^N\) (our vocabulary)

State: Current word configuration: \(\xi \in \{-1,+1\}^d\)

Energy function: \(E = -\frac{1}{2}\sum_i \sum_j W_{ij}\xi_i\xi_j + \sum_i b_i \xi_i\)

where \(b_i\) are bias terms (thresholds for each neuron).

Key Insight: Each polar/binary patterns are present on a energy landscape which is given by the weights. The model works by creating transition from one local state to the next. The weights ensure that there are clear wells corresponding to learned patterns which attract surrounding patterns.

\[\boxed{\text{Partial word input} \rightarrow \text{Energy minimization} \rightarrow \text{Complete word retrieval}}\]The functions of the model:

Learning the patterns:

-

Direct weight setting (Hebbian Learning):

\[W = \sum_{i=1}^N x_{i} \cdot x_{i}^T\]- Pros: Simple, biologically inspired, fast storage

- Cons: Limited capacity (~0.14N patterns), interference between similar words

- Example: Storing [“DEITY”, “DUSTY”] might create spurious states like “DAATY”

-

Gradient-based learning (Modern approach): Uses backpropagation to optimize storage capacity and reduce interference.

- Pros: Higher capacity, fewer spurious states, better retrieval

- Cons: More computationally expensive, requires training data

- Example: Can cleanly separate similar words like “DUSTY” vs “DIRTY”

Retrieving patterns (Update rules):

-

Asynchronous updates (Classical):

\[\xi_{i}^{(new)} = \text{sign}\Big(\sum_j W_{ij} \xi_j - b \Big) \text{(one neuron at a time)}\]- Pros: Guaranteed convergence, biologically realistic2

- Cons: Slower convergence, order-dependent results

- Use case: When you want guaranteed stability for word completion

-

Synchronous updates (Parallel):

\[\xi^{(new)} = \text{sign} \big( W \cdot \xi \big) \text{(all neurons simultaneously)}\]- Pros: Faster computation due to vectorization.

- Cons: Can oscillate, might not converge

- Use case: When speed matters and patterns are well-separated

Classical Limitations (Setting up the need for Modern Hopfield)

The fundamental problems:

- Limited capacity: Can only reliably store ~0.14N patterns

- Spurious attractors: Network might converge to “DAATY” instead of “DEITY”

- Interference: Similar words like “DUSTY” and “DIRTY” confuse each other

These limitations motivated the development of Modern Hopfield Networks, which solve these issues while preserving the elegant associative memory properties.

Some side related topics which are also very important:

- Free Energy Principle: How biological systems minimize surprise through prediction.

Imagine you’re trying to catch a ball. You make predictions about its trajectory (perception) and then take actions to move towards it (action). The FEP suggests that you’re constantly minimizing the “surprise” of catching the ball by updating your predictions and refining your movements.

- Hebbian Learning:

“Neurons that fire together, wire together” - the biological basis for associative memory.

3. Modern Hopfield Networks: Exponential Capacity and Continuous States

The classical Hopfield networks suffer from fundamental limitations: spurious attractors, limited storage capacity (~0.14N), and poor retrieval for similar patterns. Modern Hopfield Networks, introduced by Krotov & Hopfield (2016) and generalized by Ramsauer et al. (2020), address these issues through continuous states and exponential interaction functions.

Energy Function with Interaction Functions

The key innovation lies in replacing the quadratic energy function with more general interaction functions. The modern energy function is:

\[E = -\sum_{i=1}^N F\left(\frac{1}{d}(\mathbf{x}_i)^T \boldsymbol{\xi}\right)\]where:

- \(\mathbf{x}_i \in \mathbb{R}^d\) are the stored patterns

- \(\boldsymbol{\xi} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is the current state

- \(F: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is the interaction function

- \(d\) is the pattern dimension

Common Interaction Functions:

- Exponential: \(F(x) = \exp(x)\)

- Provides exponential storage capacity

- Most commonly used in practice

- Polynomial: \(F(x) = x^n\) for \(n \geq 2\)

- Polynomial storage capacity scaling

- Computational simplicity

- Custom functions: Any concave function satisfying convergence conditions

The exponential interaction function is particularly powerful because it creates a log-sum-exp energy landscape that naturally separates stored patterns.

Storage Capacity

Classical Hopfield: Capacity scales as \(C_\text{classical} \sim 0.14N\) patterns.

Modern Hopfield: With exponential interaction functions, capacity scales exponentially with dimension: \(C_{modern} \sim \exp(\alpha d)\)

where \(\alpha\) depends on the specific interaction function and pattern distribution.

Practical Implication: A 130-dimensional Modern Hopfield Network (5×26 for our word encoding) can store thousands of patterns without significant interference, compared to ~18 patterns for classical networks.

The Beta Parameter

The inverse temperature parameter \(\beta\) controls the sharpness of the energy landscape:

\[E_{\beta} = -\frac{1}{\beta} \log \sum_{i=1}^N \exp\left(\beta \frac{(\mathbf{x}_i)^T \boldsymbol{\xi}}{d}\right)\]Effects of \(\beta\):

- \(\beta \rightarrow 0\): Uniform distribution over all patterns (high temperature)

- \(\beta \rightarrow \infty\): Sharp focus on most similar pattern (low temperature)

- \(\beta = 1\): Balanced retrieval dynamics

For word completion, higher \(\beta\) values (\(\beta \geq 2\)) provide more decisive pattern completion.

Update Rule Derivation

The update rule emerges from energy minimization using the concave-convex procedure. Starting with the energy:

\[E = -\frac{1}{\beta} \log \sum_{i=1}^N \exp\left(\beta \frac{(\mathbf{x}_i)^T \boldsymbol{\xi}}{d}\right)\]Step 1: Apply concave-convex decomposition to handle the log-sum-exp structure.

Step 2: The gradient with respect to \(\boldsymbol{\xi}\) yields: \(\frac{\partial E}{\partial \boldsymbol{\xi}} = -\frac{1}{d} \sum_{i=1}^N \frac{\exp\left(\beta \frac{(\mathbf{x}_i)^T \boldsymbol{\xi}}{d}\right)}{\sum_{j=1}^N \exp\left(\beta \frac{(\mathbf{x}^{(j)})^T \boldsymbol{\xi}}{d}\right)} \mathbf{x}_i\)

Step 3: Recognizing the softmax structure: \(\boldsymbol{\xi}^{new} = \sum_{i=1}^N \text{softmax}\left(\beta \frac{(\mathbf{x}_i)^T \boldsymbol{\xi}}{d}\right)_i \mathbf{x}_i\)

Step 4: In matrix notation, with \(\mathbf{X} = [\mathbf{x}^{(1)}, \ldots, \mathbf{x}^{(N)}]\):

\[\boxed{\boldsymbol{\xi}^{new} = \mathbf{X} \cdot \text{softmax}\left(\beta \mathbf{X}^T \boldsymbol{\xi}\right)}\]Connection to Transformer Self-Attention

The update rule is mathematically equivalent to the self-attention mechanism in transformer networks:

Hopfield Update: \(\boldsymbol{\xi}^{new} = \mathbf{X} \cdot \text{softmax}(\beta \mathbf{X}^T \boldsymbol{\xi})\)

Self-Attention: \(\text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \mathbf{V} \cdot \text{softmax}\left(\frac{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\)

Correspondence:

- \(\mathbf{V} = \mathbf{K} = \mathbf{X}\) (stored patterns)

- \(\mathbf{Q} = \boldsymbol{\xi}^T\) (query state)

- \(\beta = 1/\sqrt{d_k}\) (temperature scaling)

This equivalence reveals that attention mechanisms are performing associative memory retrieval in the continuous state space.

What I Learned from Trying (and Failing) to Solve Wordle with Hopfield Networks

A brutally honest account of why biological inspiration doesn’t always translate to working code

What I Thought Would Happen

I was convinced that solving Wordle would be a breeze—just build a working MVP since I initially thought solving Wordle was a recalling game plus optimally choosing the retrieved answer. The logic seemed bulletproof:

- Humans see “d__ty” and recall words like “deity,” “dusty,” “dirty”

- This looks exactly like associative memory retrieval

- Modern Hopfield networks are basically attention mechanisms that do associative memory

- Therefore: Hopfield + some word selection strategy = Human-like Wordle solver

I figured I’d model the recall part using Hopfield networks, then use some optimization method (LoRA-based eigenvector alignment) to pick the best candidate. Easy, right?

Spoiler alert: It wasn’t.

What I Actually Built

Let me walk through what I created:

The Core Architecture

I implemented a WordHopfieldNetwork that:

- One-hot encodes 5-letter words into 130-dimensional vectors (5 positions × 26 letters)

- Uses modern Hopfield dynamics with softmax attention:

similarities = self.beta * (self.memories.T @ effective_query) attention_weights = softmax(similarities) retrieved = self.memories @ attention_weights - Applies winner-take-all decoding to get valid words back

The Memory Deletion Catastrophe

Here’s where things got creative (read: desperate). When the network kept suggesting the same words, I implemented a “suppression mechanism”:

def retrieve_possible_words(self, partial_word, unknown_char='_'):

res = []

while True:

completed_word = self.complete_word(partial_word, unknown_char)

# Find the memory pattern for this word

position = np.where(np.all(self.memories == self.encode_word(

completed_word).reshape(-1, 1), axis=0))

if position[0].size > 0:

res.append(completed_word)

# Delete the memory permanently

self.memories = np.delete(self.memories, position, axis=1)

else:

break

return res

Yes, I literally deleted patterns from memory after retrieving them. What could go wrong?

The LoRA Band-Aid

To pick the “best” word from retrieved candidates, I bolted on a Low-Rank Approximation method that:

- Converts candidate words to letter frequency vectors

- Finds the dominant eigenvector of the word-word similarity matrix

- Picks the word with the smallest angle to this eigenvector

def LSI(self, possible_words, must_haves):

A = self.word_to_vector(possible_words[0])

for word in possible_words:

A = np.concatenate((A, self.word_to_vector(word)), 1)

AA = np.matmul(A, np.matrix.transpose(A))

w, v = np.linalg.eigh(AA)

dom1 = np.abs(v[:, -1]) # Dominant eigenvector

# Find word with smallest angle to dominant direction

angle_min = 90

for i in range(len(possible_words)):

angle1 = np.arccos(np.matmul(A[:, i], dom1)/(np.linalg.norm(A[:, i])))

# ... pick best_word based on angle

This whole pipeline was held together with digital duct tape and wishful thinking.

Why It Failed Spectacularly

1. Sub-optimal Energy Minima

The network would converge to nonsensical letter combinations like “DAAEZ” or “SUUUU” because:

- One-hot encoding creates sparse, high-dimensional vectors

- Similar words (like “DUSTY”, “DIRTY”, “DEITY”) create overlapping attraction basins

- The energy landscape was littered with spurious attractors that maximized pattern overlap without forming valid English words

2. Pattern Completion ≠ Constraint Satisfaction

This was the fundamental conceptual error. Wordle isn’t about recalling complete patterns—it’s about satisfying logical constraints:

- 🟩 Green: Letter X must be in position Y

- 🟨 Yellow: Letter X must be in the word but not in position Y

- ⬜ Gray: Letter X must not be anywhere in the word

My Hopfield network optimized for: \(\text{argmax}_{\text{word}} \; \text{similarity}(\text{word}, \text{partial\_pattern})\)

But Wordle requires: \(\text{argmax}_{\text{word}} \; \mathbb{I}[\text{word satisfies all constraints}]\)

These are fundamentally different objective functions.

3. Suppression Mechanism Caused Chaos

Deleting memories from the Hopfield network was like removing neurons from a brain mid-thought:

- Catastrophic interference: Removing one pattern corrupted the retrieval of similar patterns

- Cascade failures: After suppressing ~10 words, the network couldn’t retrieve anything sensible

- Memory degradation: The attention weights became unstable as the memory matrix shrank

The network went from confidently suggesting “DEITY” to outputting gibberish like “” within a few deletions. Also a weird bug happened, the network keeps on converging to deleted patterns although it’s not presented in the memory matrix anymore.

4. Wrong Tool for the Job

I was essentially using a hammer to perform surgery. Hopfield networks excel at:

- Denoising corrupted patterns

- Completing missing parts of stored memories

- Associative recall from partial cues

But Wordle needs:

- Logical reasoning about constraints

- Search through valid word space

- Information-theoretic optimization for guess selection

What I Learned

The biggest lesson? I was solving the wrong problem entirely. I thought Wordle was about pattern completion when it’s actually about constraint satisfaction. Hopfield networks excel at recalling corrupted memories, but Wordle doesn’t give you corrupted patterns—it gives you logical rules that must be satisfied. When humans see “d__ty” and think “deity,” they’re not just doing associative recall. They’re simultaneously tracking constraints (no repeated letters from previous guesses, letter positions that are forbidden, etc.) while accessing word memory. I tried to cram this entire cognitive pipeline into a single associative memory mechanism, which was fundamentally naive. Seeing memory deletion cascade into complete network breakdown showed me why you can’t just hack biological systems with engineering tricks. Most importantly: biological inspiration doesn't automatically translate to good algorithms. Just because the brain does something doesn't mean copying that mechanism will work in silicon. The gap between cognitive plausibility and computational efficiency is huge, and I underestimated it completely.

If I Were to Do This Again…

Constraint-Aware Energy Function

Instead of pure pattern completion, I’d formulate this as constraint satisfaction with memory bias:

\[E(x) = E_{\text{valid}}(x) + \lambda_G E_{\text{green}}(x, G) + \lambda_Y E_{\text{yellow}}(x, Y) + \lambda_B E_{\text{black}}(x, B) + E_{\text{memory}}(x)\]Where:

- \(E_{\text{green}}(x, G) = \sum_{(i,c) \in G} (1 - x_{i,c})\) penalizes violating green constraints

- \(E_{\text{yellow}}(x, Y)\) ensures yellow letters appear elsewhere

- \(E_{\text{black}}(x, B)\) forbids gray letters entirely

- \(E_{\text{memory}}(x) = -\log\sum_{\mu} \exp(\beta x^T \xi^{\mu})\) biases toward real words

This wouldn’t be “pure” Hopfield anymore—it’s more like constrained optimization inspired by Hopfield. But at least it might work.

Inhibitory Fields Instead of Memory Deletion

Rather than destroying memories, research more and implement some forms of memory suppressions:

This approach might preserves network stability while avoiding repetition.

Dense Distributed Representations

The sparse one-hot encoding was problematic because:

- No semantic relationships between similar words

- High dimensionality with low information density

- Lots of local minima without meaningful structure

Better approaches:

- Letter n-gram embeddings (capture “TH”, “CH”, “ST” patterns)

- Phonetic representations (similar-sounding words cluster together)

- Pre-trained word embeddings (semantic similarity built-in)

For example, “DUSTY” and “DIRTY” should be closer in embedding space than “DUSTY” and “ZEBRA”.

Conclusion:

This project was a total failure in terms of building a working Wordle solver. The success rate was probably worse than random guessing. Sometimes the most valuable research is the kind that doesn’t work—because it teaches you why it doesn’t work, and what to try instead.

Next up: Maybe I’ll try to solve Wordle with constraint satisfaction properly, or better yet, find a problem that’s actually suited for Hopfield networks.

Code available on GitHub

References

- The paper I chose to dive deep into hopfield: Hopfield Networks is All You Need

- Video that sparked my interest in doing Hopfield Net: Hopfield network: How are memories stored in neural networks? #SoME2

- Daily Wordle: NY Times

Acknowledgement:

- Thanks my dear teammates @ HCMUS for agreeing to do my initial idea on Hopfield Networks, hope we can colab again in the future.

- Thanks Dr. Tam Nguyen @ EPFL who checked on our drafts and be my trusty information source.

- Everyone that supported me emotionally during this.

Disclaimer

-

This is proved to be inaccurate to depict how neurons works irl, example when you sit down/ stand up, there’ll be 2 seperate pathways of neurons to strengthen. For further reading, please consider a explanation video of Artem Kirsanov on “Brain’s Hidden Learning Limits”. ↩

-

The fact that neurons don’t wait for other neurons to fire at the same time as they’re constantly firing and transmiting information in realtime. The scope of temporal encoding unfortunately isn’t implemented in this project tho. ↩