In memorial of David C.Marr

Table of contents

1. Who is David Marr? A short biography

2. Tri-level of analysis

3. Missing views on `Tri-level of analysis`

4. Mechanistic Interpretability

1. Who is David Marr?

David (Courtney) Marr is a person of previous century, a cognitive scientist, a neurologist. In his lifespan, if not accounting for the years of undergrad studies, he would have around 15 years working towards actual scientific rigors, yet made foundational breakthroughs that lead to establishments of Computational Neuroscience, and have an influential impacts on Artificial Intelligence (which most people’s daily routine employ under some form or another: Recommender Systems such as Youtube, TikTok, Netflix; Chatbot, LLMs; etc etc).

David Courtnay Marr was born on January 19, 1945 in Essex, England. Unfortunately, despite being a legend in the field, we know very little about David’s childhood and elementary school years. However, as far as we know, he attended one of England’s most established schools, Rugby School, a private middle-high school, on a scholarship. Around that time he grew interest in mathematics, physics and neuroscience; particularly after reading the book “Living Brain” (1953) of Grey Walter’s.

“Young David was excited by the idea of developing a “mathematical theory of the brain,” advocating that it was a feasible notion.”

In 1963, David began his undergraduate studies in mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge, on a scholarship. After completing his bachelor’s degree three years later, he contacted Giles Brindley in the physiology department to express his desire to do his Ph.D. with him on the brain-related work he had been contemplating for a long time. Brindley advised him to spend a year reading extensively in the field to gain knowledge, which David dedicated a year to. Among his readings at that time were the works of Ramon y Cajal and the 1967 book by Eccles, Ito, and Szentágothai, “The Cerebellum as a Neuronal Machine.” After this intense period of reading, Marr felt ready for his theory, which resulted in three separate papers published in 1969, 1970, and 1971. These papers, in essence, attempted to answer one of the fundamental questions of neurobiology by focusing on three different neuroanatomical structures: How does the brain work?

The early 1970s research landscape exhibited a problematic fragmentation: artificial intelligence pursued symbolic rule-based systems largely divorced from neural implementation, while neuroscience focused on circuit-level descriptions without computational interpretations. Upon joining MIT in 1973, Marr recognized this epistemological gap from direct experience. His cerebellar cortex theory (1969) had proposed functional explanations for anatomical structure, yet he lacked a systematic methodology to relate neural mechanisms to computational objectives. His interdisciplinary credentials with formal training in mathematics (BSc, MA), a neuroscience doctorate, and active engagement with AI research, uniquely positioned him to synthesize these perspectives. Mathematics enabled precise formalization of computational-level specifications (the what and why). AI methodologies informed algorithmic-level descriptions (representations and processes). Neuroscience provided implementation-level constraints (physical substrates). This synthesis yielded the levels-of-analysis framework, formally introduced with Poggio in 1976.

2. Tri-level of analysis:

To understand how this framework emerged, we must look at the “dynamic duo” of MIT’s AI Lab. In 1973, Tomaso Poggio, a physicist and cyberneticist from the Max Planck Institute, visited Boston. He found Marr to be “sharp, opinionated, and possessing clear ideas about almost everything”. Together, they realized that the prevailing reductionist approach, trying to understand the brain by only looking at neurons, was like trying to understand how a bird flies by studying only its feathers, ignoring aerodynamics.

The framework was first formally introduced in their joint 1976 paper, “From Understanding Computation to Understanding Neural Circuitry”. They argued against the prevailing reductionist view that understanding the hardware (neurons) was enough to understand the system. They introduced the levels of analysis to bridge the gap between Poggio’s detailed biophysics (flies) and Marr’s high-level computational theory (human vision), and further extended in generality to state that any information-processing system must be understood at three distinct, loosely coupled level:

- Computational Theory (The Goal): What is the system doing, and why? What are the constraints? (e.g., The goal of a cash register is addition).

- Algorithmic & Representational (The Method): How is the input transformed into the output? What specific algorithm is used? (e.g., The rules of decimal arithmetic).

- Implementation (The Hardware): How is this physically realized? (e.g., Silicon chips, biological neurons, or mechanical gears).

Marr emphasized that you cannot separate the process from the representation. A representation is simply a formal system for making certain information explicit.

Quoting directly from Marr’s saying:

-

Vision is therefore, first and foremost, an information-processing task, but we cannot think of it just as a process. For if we are capable of knowing what is where in the world, our brains must somehow be capable of representing this information — in all its profusion of color and form, beauty, motion and detail. The study of vision must therefor include not only the study of how to extract from images the various aspects of the world the are useful to us, but also an inquiry into the nature of the internal representations by which we capture this information and thus make it available as a basis for decisions about our thoughts and actions. This duality — the representation and the processing of information — lies at the heart of most information-processing tasks and will profoundly shape our investigation of the particular problems posed by vision.

-

Modern representational theories conceive of the mind as having access to systems of internal representations; mental states are characterized by asserting what the internal representations currently specify, and mental processes by how such internal representations are obtained and how they interact.

-

A representation is a formal system for making explicit certain entities or types of information, together with a specification of how the system does this. … However, the notion that one can capture some aspect of reality by making a description of it using a symbol and that to do so can be useful seems to me a fascinating and powerful idea. … But … the choice of which to use is important and cannot be taken lightly. It determines what information is made explicit and hence what is pushed further into the background, and it has a far-reaching effect on the ease and difficulty with which operations may subsequently be carried out on that information.

In short, the representation is the state of the system, portraited by symbols used to make specific information explicit. However, information processing is the transformation of the system. It is the algorithmic rules that manipulate the representation. The ease or difficulty of a process depends entirely on the representation chosen.

Take an example for the counting system. The number “21” (decimal) and “10101” (binary) are different representations of the same abstract quantity. They make different things explicit (decimal makes magnitude clear to humans; binary makes on/off states clear to circuits). This choice matters because if you try to do long division with Roman numerals; it is a nightmare, whereas it is easy with Arabic numerals.

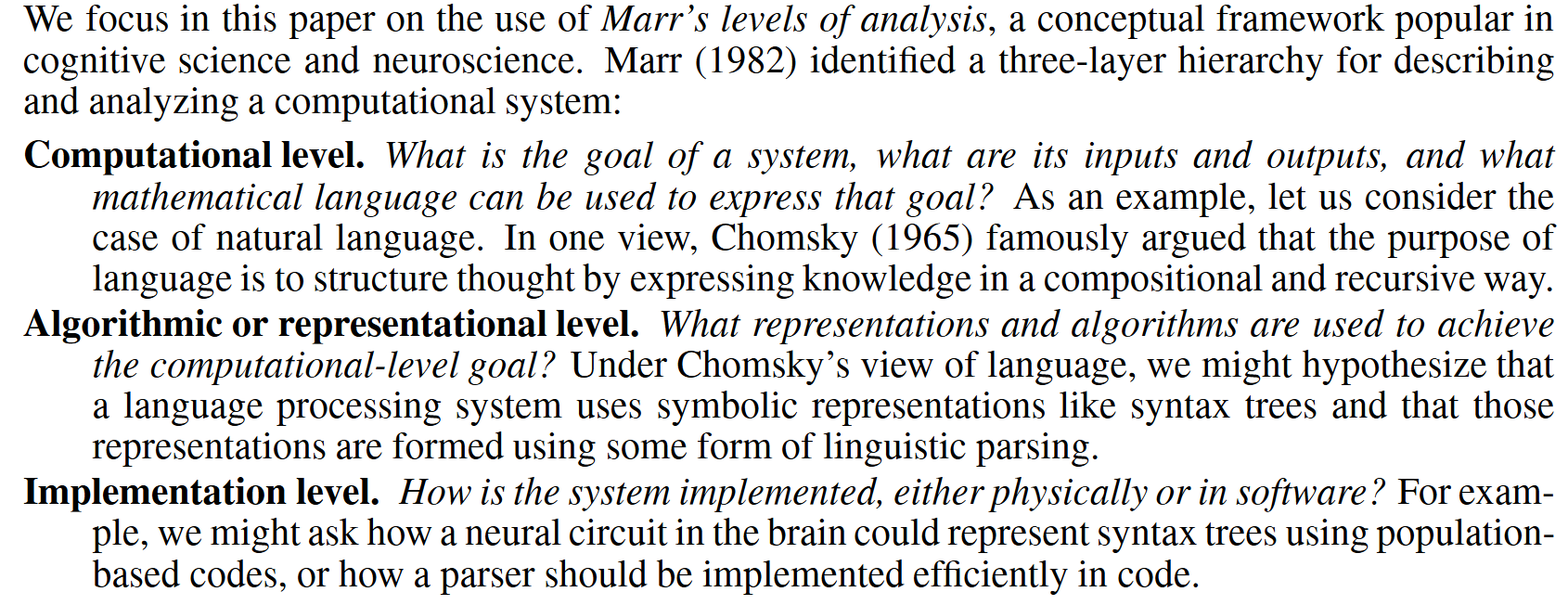

While writing this, I stumbled upon a paper titled Levels of Analysis for Machine Learning written by Google Deepmind submitted at “Bridging AI and Cognitive Science” ICLR 2020 workshop. It’s a perfect demonstration of putting Marr’s perspective (more than 50 years ago btw) to advocate a common conceptual framework that unify computer science, engineering and cognitive science into one single thread.

We can apply it to a standard Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to see how it organizes our understanding:

| Level | Question | Application to CNN (Vision) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational | What is the goal? | To map spatial data (images) to object categories (labels) in a way that is invariant to translation (moving the object shouldn’t change the label). |

| Algorithmic | How do we solve it? | Using the Convolution operation, which enforces spatial locality and weight sharing. The representation is a hierarchy of feature maps. |

| Implementation | Physical realization? | Executed on a GPU using CUDA kernels, or biological neurons firing in the visual cortex. |

Marr’s genius was realizing that these levels are loosely coupled. You can run the same algorithm (CNN) on different hardware (Implementation), or solve the same computational goal (Object Detection) with a different algorithm (Vision Transformers).

However, as we will see, Marr missed out on crucial layers that define modern AI.

3. Missing view(s) of Marr’s “Vision”

Marr’s three-level framework was groundbreaking, but it had a critical blind spot: it explained systems after they were built, not how they came to be. His levels (Computational, Algorithmic, Implementation) explain how a system works once it is finished, they fail to explain how the system got there. Marr’s original framework assumes a static, fully formed system. Poggio argues that for biological intelligence (and modern AI), the process of acquiring the algorithm is just as important as the algorithm itself, and even why there’s that process in the first place.

In Tomaso 2012’s paper, The Levels of Understanding framework, revised, he proposed the evolutionary and learning level on top of computational level.

1. Evolutionary Level: Why does this architecture exist? This level asks what environmental pressures shaped the system. Marr analyzed constraints like “surfaces are smooth” (for stereo vision). Poggio argues the ultimate constraint is deeper: “functions in nature are compositionally sparse.” The physical world is hierarchical; photons create edges, edges form shapes, shapes compose objects. Evolution selected brains with deep layered architectures because they mirror this hierarchical structure of reality itself. This explains why both cortical columns and convolutional neural networks share the same “deep hierarchy” design: they’re solving the same compositional problem.

2. Learning Level: How is the system constructed from data? This level examines the mathematical principles of generalization, how a system extracts universal rules (“objects are permanent,” “gravity pulls down”) from limited, noisy examples. For biological brains, this involves developmental plasticity and synaptic learning. For artificial networks, it involves optimization algorithms like Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). Poggio proposed that the learning algorithm itself acts as an implicit regularizer, favoring simple, generalizable solutions over complex memorization.

The Extended Framework:

- Evolutionary: Why this architecture? (Compositional structure of nature)

- Learning: How is it acquired? (Generalization from data)

- Computational: What goal does it solve? (Edge detection, face recognition)

- Algorithmic: What representations/processes? (Convolutions, transformers)

- Implementation: What hardware? (Neurons, GPUs)

Defining these new levels hasn’t been straightforward. Poggio’s theories have sparked intense academic debates about whether his mathematical frameworks actually explain deep learning’s success, or merely describe it in elegant language.

Poggio’s team argued that SGD implicitly regularizes networks, preventing overfitting even when models have billions of parameters. But in 2017, a landmark paper by Zhang et al. (“Understanding Deep Learning Requires Rethinking Generalization”) challenged this entire premise. They showed that deep networks can perfectly memorize datasets with completely random labels, where no pattern exists to learn. If Poggio were fully correct that SGD favors simplicity, networks shouldn’t be able to memorize pure noise so easily. Yet they can memorize noise (fitting random data perfectly) but don’t memorize real data (generalizing well instead). This suggests that “implicit regularization” alone might be insufficient and that something else determines when networks generalize versus memorize.

Moreover, Poggio argues that deep learning works because it exploits the compositional structure of our universe. Critics, however, point to a critical gap: representation ≠ learnability. Just because a function can be represented compositionally doesn’t mean it’s learnable through gradient descent. Take cryptographic functions for example. They’re compositional (hierarchical combinations of simple operations). At its core, a cryptographic function (like AES or SHA-256) is just a composition of simple math operations. Layer 1: Take input bits, XOR them with a key. Layer 2: Shuffle the bits (permutation). Layer 3: Swap bits using a lookup table (substitution). Repeat 10-14 times. In terms of local, hierachical and compositional properties, DNNs should be able to work on AES but it doesn’t.

Far from retreating, Poggio’s Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines has doubled down. In July 2025, his team published “A Theory of Deep Learning Must Include Compositional Sparsity,” mathematically linking compositionality to fundamental computability theory. They proved that any efficiently Turing-tractable function can be represented as compositionally sparse, suggesting deep learning works because it aligns with the deep structure of computation itself.

So in conclusion, Marr gave us the language to describe intelligence. Poggio extended it to explain learning and evolution. But the full story of how blind optimization discovers intelligent structure is still being written. As we’ll see next, this expanded framework sets the stage for an entirely new field: *Mechanistic Interpretability, the discipline of reverse-engineering what modern AI systems have actually learned.

4. The birth of Mechanistic Intepretability

Marr’s tri-level framework was designed to explain how systems work once they are built. But deep learning created a new challenge: systems that work brilliantly but remain opaque about what they’ve actually learned. A language model can translate poetry or a vision model can identify objects, yet neither we nor the researchers who built them can articulate which internal computations solve these tasks. In Marr’s terms, we have implementations (billions of neural parameters) but lack a clear map of the algorithmic level; the actual features, representations, and algorithms the network uses.

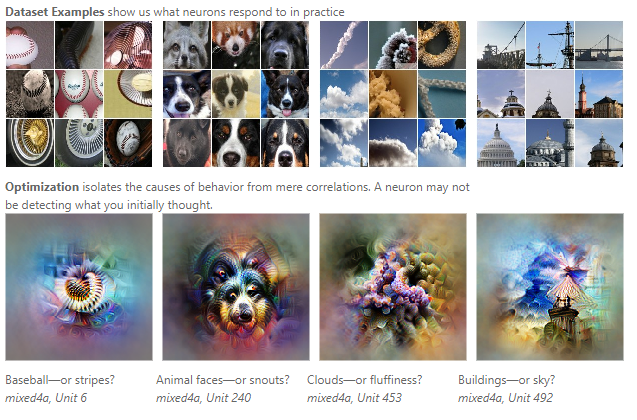

So just what is Mechanistic Intepretability (Mech Interp), then? It was coined by Chris Olah, a technical staff at Anthropic (Awesome blog go check it out, Home - colah’s blog Colah’s Blog). It’s established to reverse the state of ambiguity in Neural Nets into Marr’s framework. Rather than treating deep networks as black boxes, where we only care about inputs and outputs, mechanistic interpretability opens the box and asks: What algorithms have been learned? What features do neurons represent? How do these features compose into circuits that solve tasks. More onto that here.

The field treats neural networks like compiled computer programs. Just as a programmer might decompile machine code to recover the original logic, mechanistic interpretability attempts to recover the logic learned by gradient descent from billions of weights. This means identifying two core structures:

- Features: Interpretable concepts that neurons or groups of neurons encode. In a vision model, a feature might be “fur texture” or “curved edge.” In a language model, features represent abstract ideas like “is this referring to the subject?” or “does this context suggest deception?”

- Circuits: Sparse subgraphs of the network, specific patterns of weighted connections, that implement algorithms on those features. Famous examples include “induction heads” in transformers, which enable models to perform in-context learning by recognizing repeated patterns and predicting what comes next.

Mech Interp utilizes Marr’s framework in a way he never could with biological brains. Consider a GPT model detecting grammatical subject-verb agreement: * Computational Level: Identify the correct subject for a verb in complex sentences (why this matters: sentences with multiple potential subjects require disambiguation) * Algorithmic Level: The model uses an attention-based mechanism; specific attention heads track “name mentions,” and other heads suppress wrong subjects through mutual inhibition. * Implementation Level: These circuits run on GPU tensors. And for Poggio’s newly added layers, we could ask ourselves “Why does this circuit form? What inductive biases or compositional properties of the task make this algorithm a natural attractor for gradient descent?”

But the fact is, this field are facing a scaling challenge. Researchers have successfully reverse-engineered circuits in small models (roughly 1M–410M parameters) with algorithmic tasks like modular arithmetic, greater-than comparisons, and even some natural language phenomena like subject-verb agreement. But current techniques struggle with larger models (billions of parameters) and messier, real-world tasks.

Further details could be directly refered to Neel Nanda’s blogpost.

Wrapping Up:

This post was written in memorial of David Marr. I respect the way that he devoted for science until the last breath. May his soul rest in peace.

I wrote this blog post to anchor myself against the definition of current AI trends. I wanna understand how the brain works and how to derive useful mechanisms from it (as it’s the only source of general intelligence the world possesses currently). I hope many people will be more concerned on this matter in the future to push intelligence replication as one of 21st century profound inventions. Thank you for reading until the end:D

Appendix

A. Chronological Biography: Key Turning Points

1945–1966: Early Formation

-

January 19, 1945: Born in Essex, England

-

1957–1963: Attended Rugby School on scholarship; developed interests in mathematics, physics, and neuroscience after reading Grey Walter’s The Living Brain (1953)

-

1963–1966: Undergraduate in mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge (scholarship)

1966–1971: The Neuronal Years

-

1966–1967: Intensive year of reading (advised by Giles Brindley) including Ramón y Cajal’s neuroanatomy and Eccles, Ito, and Szentágothai’s The Cerebellum as a Neuronal Machine (1967). This shaped his theoretical approach to neural circuits.[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih]

-

1967–1971: Combined MA/PhD at Cambridge under Brindley, focusing on “How does the brain work?” Produced three landmark papers proposing computational theories of cerebellar cortex (1969), cerebral neocortex (1970), and hippocampus (archicortex, 1971).[thecognizer]

1972–1973: The MIT Turning Point

-

May 24–26, 1972: Attended brain theory workshop at Boston University where he met Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert. This encounter redirected his career toward AI.[academic.oup]

-

November 21, 1972: Received famous invitation letter from Minsky/Papert: “This is a formal invitation for you to come for three or six months or more if you want. The salary is $1,250 a month. Requirement: Do something terrific!”[thecognizer]

-

1972–1973: Brief stint at Francis Crick’s MRC Molecular Biology Laboratory (referred by Sydney Brenner)

-

1973: Moved to MIT AI Lab with KLUMSY proposal (robotic arm sensorimotor control); proposal rejected, interest shifted to vision[shimon-edelman.github]

1973–1976: Birth of the Tri-Level Framework

-

1973: Met Tomaso Poggio at MIT; beginning of the “dynamic duo” collaboration.

-

1975: Accepted permanent faculty position in MIT Psychology Department

-

1976: Established “vision group” with Poggio, Shimon Ullman, Ellen Hildreth, and Keith Nishihara

-

1976: Published “From Understanding Computation to Understanding Neural Circuitry” with Poggio—first formal introduction of the tri-level framework[bionity]

1977–1980: Racing Against Time

-

December 2, 1977: Diagnosed with acute leukemia

-

1977: Promoted to tenured professor in MIT Psychology Department

-

Summer 1979: Completed manuscript for Vision: A Computational Investigation

-

1979–1980: Despite illness, vision group published ~120 papers during this period[thecognizer]

-

November 17, 1980: Died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, age 35

-

1982: Vision published posthumously by MIT Press; became foundational text for computational neuroscience

B. Selected Publications (Chronological)

Early Neural Theories (1969–1971)

-

Marr, D. (1969). A theory of cerebellar cortex. Journal of Physiology, 202, 437-470. [First proposal of motor learning theory, predating experimental confirmation of Hebbian plasticity]

-

Marr, D. (1970). A theory for cerebral neocortex. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 176, 161-234.

-

Marr, D. (1970). How the cerebellum may be used. Nature, 227, 1224-1228. (With Stephen Blomfield)

-

Marr, D. (1971). Simple memory: a theory for archicortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 262, 23-81.

Computational Vision Era (1974–1982)

-

Marr, D. (1974). The computation of lightness by the primate retina. Vision Research, 14, 1377-1388.

-

Marr, D. (1975). Approaches to biological information processing. Science, 190, 875-876.

-

Marr, D. (1976). Early processing of visual information. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 275, 483-519.

-

Marr, D., & Poggio, T. (1976). Cooperative computation of stereo disparity. Science, 194, 283-287.

-

Marr, D. (1976). Analyzing natural images: a computational theory of texture vision. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 40, 647-662.

Landmark Theoretical Papers

-

Marr, D., & Poggio, T. (1977). From understanding computation to understanding neural circuitry. Neurosciences Research Program Bulletin, 15, 470-488. [First formal presentation of tri-level framework]

-

Marr, D. (1977). Artificial intelligence: A personal view. Artificial Intelligence, 9, 37-48.

-

Marr, D., & Nishihara, H. K. (1978). Representation and recognition of the spatial organization of three-dimensional shapes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 200, 269-294.

-

Marr, D., & Poggio, T. (1979). A computational theory of human stereo vision. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 204, 301-328.

Edge Detection and Low-Level Vision

-

Marr, D., & Hildreth, E. (1980). Theory of edge detection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 207, 187-217.

-

Marr, D. (1980). Visual information processing: the structure and creation of visual representations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 290, 199-218.

-

Marr, D., & Ullman, S. (1981). Directional selectivity and its use in early visual processing. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 211, 151-180.

The Magnum Opus

-

Marr, D. (1982). Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. W. H. Freeman. [Published posthumously; reissued by MIT Press, 2010]

-

Marr, D., & Vaina, L. M. (1982). Representation and recognition of the movements of shapes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 214, 501-524.

C. Intellectual Evolution

Phase 1 (1966–1972): Neuronal Reductionism Marr believed “truth was essentially neuronal“—that understanding circuit wiring would explain function. His cerebellar theory exemplified this approach.[thecognizer]

Phase 2 (1972–1976): Computational Awakening The MIT environment and collaboration with Poggio shifted his focus from “how neurons connect” to “what computational problems they solve”. This led to the tri-level framework.

Phase 3 (1977–1980): Vision as Information Processing Diagnosed with leukemia, Marr raced to complete his comprehensive theory. Vision synthesized eight years of work into a unified framework treating perception as computation.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: